Safety.

This is a huge subject; well and beyond the scope of these pages. Honestly, I'd like to think about the topics here as a more general or abstract overview of these old apparatus, something that takes an approach a little different than a picture and brief description or price tag. That said, it's really difficult to discuss these things without mentioning potential hazards and some good work bench habits. My point here is that this safety section is incomplete. I do not intend this page to be a definitive tutorial on the subject, and urge anyone to seek a more formal training or education on it before proceeding with your project.

Common sense. Let's step back a bit and assess the situation. Common sense isn't something you're taught, it's something you learn.

Here are the fundamental aspects I keep in mind while working with one of these things:

These operate with a high voltage.

Electricity is usually invisible.

It's highly likely the parts keeping the high voltage from spilling over to someplace it shouldn't be have been quietly aging or decomposing for decades.

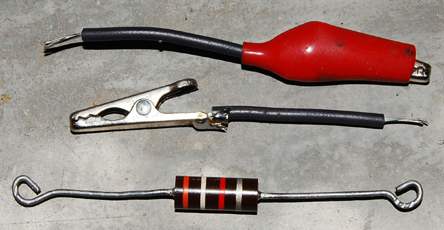

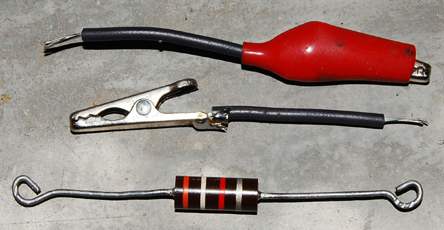

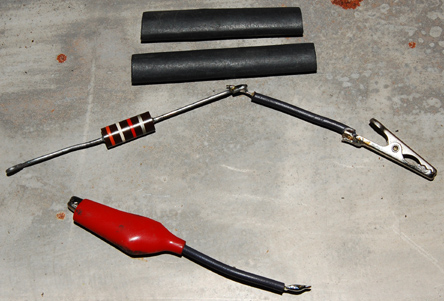

Discharging capacitors. In the event something you've cracked open is lacking trickle down resistors, or is suspected of harboring stray voltage for other reasons, a jumper similar to the one shown is handy. Pieces here are two alligator clips soldered to leads (a bit on the short side), heat shrink and a 3K9 one watt resistor. I prefer resistors over 1K for this, as the goal is to avoid a spark from abrupt discharge, which I understand as hard on the components (not to mention hard on what actually arcs). I feel the sequence of photos is pretty self explanatory, so without further ado:

I opt to hook the uninsulated lead to ground and connect to the charged point with the insulated side. I tend to leave it connected for the duration of time I am messing around with the innards. Do remember to remove this prior to powering the circuit up again.

Many of these devices were also built in an era where most people were blissfully unaware of many or all of the negative effects from compounds such as lead, mercury, asbestos and PCBs (PolyChlorinated Biphenyls). That is an incomplete list of the sort of nasty shit that you may very well run across while poking around inside these things; so in addition to exerting caution that should be standard around charged circuits, do limit exposure with failed parts removed, etc.

Unless they say otherwise, expect oil filled caps like this to contain PCBs.

In this shot, I can guarantee those solder joints are lead bearing, expect that compound that is leaking out of that failing electrolytic contains PCBs and wouldn't be surprised if the cloth sheathing on those wires contains asbestos. I don't say this to alarm anyone, just more justification to leave well enough alone and try to keep this stuff out of the landfill.

Since I'm already on the topic of hazardous materials, I guess I should address the touchy subject of disposal. My approach to disposal is to toss failed and nasty stuff into a 5 gallon bucket. When the bucket is full I will simply dump it into a frame containing some previously created piece of art or other, encase the whole thing in a clear silicone, epoxy or urethane of some sort and either admire it or trade it to someone for goods or money.

Another viable approach would be to take the pail of hazardous material to a depot designed to deal with household hazardous waste. Simply throwing these into the trash, burning them or burying them in your yard is almost as irresponsible as grinding them up and feeding them to loved ones, and is a tactic best avoided.